Grand Trunk Express, 2004

Chennai

The road to Pakistan begins in Chennai. Invitations, documentation scanned and emailed back and forth, the paper planned, the paper struggled over, the paper written and finished almost breathlessly—all happen at the faraway, hot, humid, other end of this civilisational area.

There is something utterly unreal about going to Pakistan when you sit in Tamil Nadu. Of course, people from South India travel to Pakistan and some Pakistanis even make the trip south of the Vindhyas. Nevertheless, in a place where Delhi seems far away, Pakistan is that much further. And yet, in the last eighteen months, my friends in Islamabad have been closer at hand than friends located at shorter distances, thanks largely to the telecommunications revolution across South Asia.

So it’s Sunday, and I am scheduled to leave for Delhi in the morning. I have tried to plan and pack systematically for this trip, partly to proactively counter that dread of things not working out at the last minute. “Be positive, affirm it is happening and it will happen.” So I have shopped, and dry cleaned, and packed. The last minute is always a scramble no matter what you do, and so it’s Sunday and I am still scrambling. Butterflies are flying dizzily in my stomach—not about being in Pakistan but about getting to Pakistan, which will involve visa-related activities in Delhi. And like many people, I hate dealing with officialdom—when all else fails, it is the possibility of a world without visa regulations and other scary airport strictures that keeps the peace activist in me alive.

Delhi Darbar

Courage and cunning won Shivaji success in his Deccan confrontations with the armed sardars of the Mughal Empire. This rebel leader was surely carving out his own kingdom, by reclaiming chunks of territory. Finally, Emperor Aurangzeb invited him to the court at Delhi. Shivaji had inherited a mansabdari (feud) of 1000 horses, and he was an important personage in his own right as the emerging leader of the Maratha peoples. He expected to be accorded special treatment, but to his indignation was made to stand in the back of the durbar with other low-ranking mansabdars. Moreover, he was placed under house arrest for protesting, and then got himself smuggled out of his prison in a basket of sweets.

Raised in Maharashtra, this story has been part of my consciousness virtually all my life, and working or traveling on work to Delhi brings it to mind. The story resonates and I feel Shivaji’s alienation afresh each time I ask a colleague for an appointment and am told to wait. I am no supplicant, Shivaji’s voice says within me. I am your equal and I am here and seeking to call on you out of courtesy. It resurfaces when I have to get letters of introduction for this or that, and when I run into that rubber wall of the everyone-knows-everyone circle and get bounced off.

Coming from Bombay, I also carry with me a sense of contempt for Delhi and its workings. The slowing but still dynamic energy field of my native place makes everything else appear provincial. And Delhiities know this: in spite of their new flyovers and CNG scooters, gargantuan and shiny malls, and the cosmopolitan dining options available, the chip on their shoulder is Bombay—the endless comparison of self to better is, to me, usually amusing, sometimes tiresome.

Coming from Bombay, living now in Madras, the distance from Delhi has doubled literally and culturally, even though my work now brings me here often and to enjoyable meetings (yes, actually!). With the sense of alienation deepening upon contact, little wonder that the issues I choose to study are all issues relating to alienation and integration, to nuanced redefinitions of belonging and exclusion and to being embraced or left out.

So anyway, I am in Delhi. Navigating its beautiful broad avenues as I go back and forth taking care of travel arrangements that were impossible to make from Chennai—another distancing—I hear about things that people assume I knew. That I would have known or that may have been easier had I been located here. Summoning up my very little patience as I respond to each “should have known better,” I get past the two days of paperwork and waiting for paperwork.

Journey to Pakistan

I am going to Pakistan. Finally.

The “Indian in Pakistan” experience begins in the security enclosure, where a quick glance suggests that we sit segregated along class lines. I have chosen to sit near a group of elderly Sikh travelers, who have been smiling at me all the way from check-in past security. As I start reading my book, one of the gentlemen comes over and asks, “Are you from India or Pakistan?” Smiling, I ask him to guess. He looks at me thoughtfully for a while and says, “Somewhere in between.” In a way, he is right.

A small community of professionals from the region is now acquiring this additional trans-state identity, which is at once a return to the past and the harbinger of the future. Insofar as it is anchored in shared tastes and shared habits it is a return to the past. In its desire to reach across more recently defined frontiers, it is a return to the past. But because those frontiers are already being undermined by other things like telecommunications and trade, it is the harbinger of a future in which state affiliations and state boundaries will be administrative and functional conveniences rather than airtight containers within which the aspirations of a people might be sealed.

For members of this community—who are academics, writers, civil society activists, mediapersons, and even government servants—a second identity adorns the first nation-state one, rather like shadowing or embossing adorn a letter in regular font. We are Indians, or Pakistanis, or Bangladeshis, etc. But we are also South Asians. And we choose to celebrate what we share and to nurture the commonalities as much as recent history has underscored our differences.

So I am from somewhere in between. As he is, too. He is easier to peg, a Sikh from pre-partition Lyallpur (now Faisalabad) and Lahore. He and his siblings are visiting Pakistan for the first time after Partition. They will visit Lahore and Faisalabad, speaking to students at their old schools and colleges.

Kinnaird College at Lahore has played an important part in fostering such exchanges. Kinnaird alumni regularly go back and forth across the border in reunion programs. By bringing the nostalgia of one generation into the reality of the other, these reunions soften the animus that the education systems and media of the two countries otherwise foster, wittingly or unwittingly. This is a model that North Indian institutions might emulate.

We have exchanged life-stories and as I get up to walk over to the rest-room, I am greeting by another couple, who are extremely elegantly dressed. She is in wearing clothes from a store whose name becomes very familiar to me over the weekend—Bareezé. They have been sitting in the vicinity. They smile at me and ask whether I am going to Pakistan or returning to Pakistan. As we exchange pleasantries, they tell me they have been visiting India under the auspices of a program that has brought retired military officers from Pakistan over. They have had a wonderful time.

This is the good news. We hear the bad news all the time about incursions, insurgencies, press statements, denials, accord violations, etc. The good news is that quietly, continuously, without the glare of publicity, people are meeting each other in programs like this all the time now. Person by person, kindness by kindness, we will build a new South Asia.

Soon all of us are talking together, exchanging addresses. The Pakistani couple offer shopping recommendations and say, “We are there, if you need anything.” None of us is likely to call them, but it is really that thought that counts—in interpersonal and international relations: We are there, if you need anything.

At Lahore airport, we are on the terminal-bound bus and a young woman says to me, “You will be really cold. The wind from the mountains is really cold in Islamabad.” I assure her that I am carrying woolens in hand. Later, as I claim my bags, she slips her mobile number in my hand, saying, “I am from Islamabad, if you need anything, if you have any problem, call me. This is my mobile number.” I am touched. But this is only the first of many, many unbidden kindnesses I will feel.

Before I can react to my surroundings, a whirlwind swoops down on me in the form of a blue-coated ‘Passenger Facilitator.’ Do I have another flight to catch? Do I need to go to the domestic terminal? The whirlwind sweeps me through security, security, check-in and when I finally comprehend, he says to me in Urdu, “You can now pay me.” I stutter, stunned, that I have not changed my money, and he impatiently assures me that it is not important. He will take Indian rupees or any other currency.

I retire to the empty security lounge which is beautiful. Shiny and new, it is also clean but sadly devoid of those ‘time-pass’ features like shops and cafes. By South Asian standards, it is just beautiful.

And you can take the South Asian out of the bazaar but not the bazaar out of the South Asian! No sooner have I entered than does a smiling young man approach me. Do I want to make a phone call? Local? Mobile? International? No problem. He has a stack of calling cards and will let me use them for a price. I reiterate that I have not been able to change my money yet and again, Indian rupees pose no problem. They are also accepted by the tea-stand which is stacked with all sorts of goodies. I order tea and am served a sandwich as well. Unsure of the currency question, I refuse the sandwich. After five days in Pakistan, it occurs to me that was just on the house!

The sharp business acumen shown in these transaction amuses rather than angers. All the vendors accept Indian rupees and return Pakistani. This is fair enough. However, the price of this transaction is that there is no exchange rate conversion involved, and my hunch is that this favors them more than it does the Indian customer.

On the Islamabad flight, I am seated next to an articulate geologist. A pattern is already beginning to emerge in my conversations with Pakistanis on this trip. First, we talk about how much we have in common. This can take a long time because, really, we do have a lot in common. Then we speculate in the most diplomatic terms we can muster about the factors that keep us separated. This is conducted in tones of great regret, always, and ends quickly before anyone is forced to try and pin blame. Pakistanis want to know what Indians think of them. And are Indians hopeful of the thaw in this relationship? The anxiety about the answers is not veiled. Then we move on to other topics or lapse into silence and the five decade history of confrontation sits between us like a large elephant.

An abbreviated version of this exchange goes thus:

“Are you from India? India mein kahaan?” Yes. Bombay and Chennai.

“Have you liked Islamabad?” Yes, very much. It is very pretty.

“And Pakistan.” Very much. What is not to like?

“And Pakistanis?” I cannot contain my smile at this eager question that I encounter repeatedly.

My reply: “Even more.” I know I have made my interlocutor’s day!But I am getting ahead of my story here.

Chiffon and lace

I would love to own a Pakistani salwar-kameez suit. From the early 1980s and watching PTV serials, I have admired the variety of their designs and well-cut elegance. But here I am with two spare days, recovering from my recent spell of bad luck with Chennai tailors and thinking: this is not going to happen on this trip. I cannot fit ready-mades easily and no tailor is that efficient.

Salt in my wounds, then, all the lovely salwar-kameezes at the conference. The beautiful prints. The flowing chiffons. The crisp silks and cottons. The delicate lace and ricrac trims on the dupattas. My regrets are only tempered by the knowledge that many of these cuts would not suit me, that the fabric would be sweaty and stinky in Madras and that the design is generally utterly at odds in the ethos of the Madras streets I usually traverse.

Pakistani women are even better-groomed and better-dressed than Delhi women. Their cottons are crisp. Their chiffons never flow in defiance of their cut. Their hair is coiffed, their hands don’t chap and their nail-polish doesn’t chip.

I have chiffon and lace envy with a vengeance.

Conferencing clues

Anyone who has attended a handful of conferences knows that a conference is not to be judged by the panels held and papers presented as much as the connections made and the publications available at the book sales.

The American Political Science Association’s annual meeting is the stuff of nightmares. Thousands throng the venue, many of them graduate students with hearts full of hope and heads full of dread. This is their “meat market,” the term used for academic conferences where interviews are held for faculty positions. They file their portfolios and check their emails anxiously, hoping to be interviewed by at least one potential employer. The halls where the computer banks are placed, where the candidates wait and the interviews are held are thick with anxiety and misplaced ‘wisdom’ on what works and what doesn’t. Each year, there are a few lucky graduate students who interview with several schools and many who don’t get a single call. I have been in both positions and remembering the process—on either occasion—still brings back a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach.

Even without the baggage of the job search, this is a conference where almost everyone feels alienated. The size is partly responsible but organizational culture accounts for it too. Minority and international scholars lurk in its margins. Those who study politics outside the US may as well be sitting outside the US for the duration of the conference for all they are a part of it. And those whose work does not involve datasets, statistics or prognoses of immediate disaster, you really shouldn’t have…! For those, who like me, fit all three categories, the annual APSA meeting is quite simply, not much fun.

I was lucky though to discover two important ways to salvage the experience. I will share them here for others as unfortunate as myself. The first was to make the massive book exhibit the focal point of the conference experience. For people who can spend a day in a bookstore, this is no hardship. Further, when you linger near books that are interesting to you, you will meet others who are interested in them as well. Conversations happen and lo and behold, you are networking! Finally, other nice people follow the same strategy and you may even make friends. The second salvage method is rooted in human psychology and physiology. Conferences are places where people stand around and mill. If you sit down somewhere, you break the apparent taboo against sitting, and relieved people with tired feet and backs, come sit with you. Some of them are interesting, and some may even be important.

I have dressed both the preceding ways in the garb of utility. Focusing on utility, however, you can at best salvage a conference. If you want to enjoy the conference, forget the conference, the networking and professional advancement altogether. Meet old friends and make new ones. The best conferences I have been to were all places where this happened. I do not remember earth-shattering intellectual discoveries; I remember moments of warmth and moments of laughter.

Am I saying that scholarship has nothing to do with the success of a conference? Of course not. Focused, small conferences where the agenda is somewhat structured and everyone is prepared are incredibly stimulating experiences. And even the large alienating ones can be redeemed by a good round-table or theme panels.

Rendezvous

The conference I have come to attend in Pakistan more than meets the people criterion. I have met several people whose work I have found interesting, others with whom I have corresponded and the special few who have become close friends without our ever meeting. They are all temptations leading me out of the stuffy and overheated conference halls into stimulating conversations and diverting excursions.

I

A short walk leads us into this open-air food court. The air is blessedly cool and crisp and we have been enough suffocated that two of us opt for cold aerated drinks over tea. I want to say the food court is clean but if I choose to look at the ground or at the table, I know I would find otherwise. So I pretend it is clean and my eyes wander to absorb the layout of the market, whose straight lines disguise their discontinuous design.

Around the table are an assortment of scholars—an educationist, two historians and two political scientists. The conversation resumes where a previous one, unattended by everyone present left off but the cool breeze and warm camaraderie do not fail to inspire. We are animated and articulate in seconds.

“Is colonialism responsible for the creation of religious communities in the region?”

“Do we understand the frameworks of faith adequately?”

“Who has the right to write and interpret these matters?”

“Is what matters most, the intention or the act itself?”

“Who takes responsibility for the creation and policing of a particular paradigms?”

“Policing of academic discourse creates a culture of mediocrity. Is it possible for learning to take place in the circumstances?”

“What is theory and what is doctrine?”An hour passes and none of these questions is answered but we all know each other a little better now. Reluctantly, we get up and proceed, some towards the conference venue and others towards the market.

II

We have passed notes back and forth, first taking advantage of the fact that the seat between us was unoccupied and then in spite of the tall, well-built and formidably serious gentleman who has chosen to occupy it. As with giggling schoolgirls, the newly laid obstacle course moves our notes to greater lengths and the letters are passed behind the back of the stalwart scholar with increasing frequency. At length, the people we have come to hear get their turn and we leave right after that to continue our conversation orally.

“I have been wanting to meet you for years.”

“Have we not met? I thought we had.” “But this is not a new conversation either.”

“Is this your field of work?”

“Is this your spiritual practice?”

“This is what gives my work meaning, that it should be the voice of someone who would otherwise lack a voice.”

“This is what gives my life meaning, that my work should speak to another’s need.”Some friendships resume at unknown points of rupture. In my blessed life, I have known many of them.

III

Within minutes, the taxi has left behind every sign of the planned Pakistan capital city, and our road seems forest-lined. Nestling in a well-chosen clearing and framed artfully by hills and trees, sits Islamabad’s Lok Virsa museum. This museum of folk arts is a celebration of life itself, with all its material fullness and ethereal aspirations.

Above: Lok Virsa museum

Below: Museum entrance foyer ceiling.

In the yard are placed modes of transport, decorated in the local style, including the very distinctively painted trucks of Pakistan. As I wait for my deliciously hot tea to cool to a drinkable temperature, I wander the yard with my camera. Other structures in the compound replicate the simple mud houses of the North Indian (North South Asian?) plains, not an unusual fashion for such complexes in the region. In fact, the act of choosing to replicate everyday structures and styles in museums is a political choice to move away from the imposing structures in which colonial rulers housed their exotic war spoils and state gifts. But again, I get ahead of myself. What I wanted to write about are the beautiful wood-carved doors at the Lok Virsa museum.

Many of the structures in the compound appear not to house anything in particular, or it could be that it was a particularly sleepy morning we were there. However, all of the low mud structures were studded with these exquisite doors that must have belonged to havelis all over Pakistan. If this quality of artistry is still available in Pakistan, it is to be hoped it is celebrated and receives patronage. I photograph them knowing full well that they will look nowhere as exquisite as I see them. The doors presage what lies ahead.

Above: Restored haveli doors.

Below: Close-up of door on right.

It is hard for scholars to leave the habit of critical thinking behind. In our tired moments, what remains is the habit of criticism alone. Indeed one might ask what the difference between the two is, and in our speech and behaviour, we certainly leave the question open. I cannot speak for my companions but fortunately for me that day, my mind simply surrenders to the pleasures of colour, shape and texture that lay before me.

Before the surrender is possible, we must walk through a few exhibition panels on the history of Pakistan through time. These are conceived beautifully, juxtaposing replicas of the best-known remains of earlier periods (such as the Mohenjo-daro dancing girl and head priest) with recreations of present day material life—hut facades, pots and pans, textiles. Mohenjo-daro and Gandhara yield to a depiction of Pakistan as the cross-roads of Asia. Even someone like me, who does not want to pick faults in the face of the generous hospitality I am enjoying, cannot but notice that Pakistan resolutely ignores any roads leading from the cultures of the Gangetic plains. The Lok Virsa museum, notwithstanding its later embrace of Dharwar-based Indian performers like Bhimsen Joshi, confines the association of Pakistan’s culture with South Asia’s ‘Hindu’ cultures to one stray mention that the Rig Veda was composed on the banks of the Indus. I should also mention that the recreated Thar home has a flute-playing Krishna within its mud walls. Nevertheless, even liberal institutions cannot escape the intellectual strictures of the nation-building project.

I know this piece will have readers who will pounce on this one statement of mine and ignore all the hundreds of other nice things I have to say about Pakistan. To them, I will say this as well: all diverse societies pay a heavy (too heavy) price for the simplifying process of nation-building. India’s endless textbook controversies are one case in point, not to mention the Ram Janmabhoomi conflict. In this case, it is not India or Hinduism that pays a price but ordinary Pakistanis—like the college group from Murree doing the rounds when I was. They will never learn that the heritage of Ajanta-Ellora or Kashi are theirs as much as Mohenjo-daro, Taxila and the compositions of Sindh’s sufi pirs are mine. They cannot exult—with ownership—in the greatness of things outside their contemporary political boundaries because someone’s vision of history and civilization was too narrow to accommodate them.

I walk on. Time is short and the museum is large. A few steps and my senses completely take over my brain. A short passage of intense color and texture follows as I look at dhurries and shawls from all over Pakistan. Then, baskets follow. The more stark the landscape, the brighter the colors of material life.

What makes Lok Virsa an exceptional museum—by any standards, but certainly by regional ones—is the attention to detail. The curators have recreated scenes from everyday life in every part of Pakistan, and these are rich enough that you can stand there and make up your own story about the figures who stand or work or talk within these panels. You enter and exit, as briefly or at length, the lives of real people. Even as ethnographic museums go, this is a museum that showcases a peopled heritage, not one made of baskets and bricks and bronze caskets in isolation of their producers and users.

The same attention is visible in the sections that depict the “Pakistan as cross-roads” idea. In the corridor where the Central Asian section is kept, the ceiling is divided into panels, and each panel is painted in a different regional style. Likewise, the wall tile varies in certain places, juxtaposing different kinds of paneling.

This cloud of beautiful things—that actually make something romantic of rustic realities—bursts into two ‘rooms’ that describe the ‘vision of the future.’ This vision begins with the important role that Fatima Jinnah played, and then shows Pakistani women in many spheres of life. Quite honestly, I pay little attention because my word-infested soul has been in wordless beauty heaven and does not want to return.

I cannot really begin to describe the richness of this museum because honestly, the almost two hours I was there were hardly enough to comprehend it fully. If you have a chance to be in Islamabad, this is a must-see experience. Do not miss it.

Two footnotes remain.

First, we have to pay the entrance fee for foreigners at the museum. This does not bother me in itself, but I must write here about how outraged the guards at the museum were and how apologetic the young people at the ticket counter. The latter were merely enforcing a rule. The former could not believe it applied to us. Indians were not foreigners, after all. Really, it is only the thought that counts. I will remember that sentiment long after I forget the fee I paid.

Second, inside the museum, on the right are two small rooms. One is occupied by a wax-painter of some repute. Few people remain that practice this craft that, in all verity, would have not caught my eye had I not chatted with the artist for a little while. Riaz Ahmed’s skills have been recognized widely and his UNESCO citation and photographs with the arbiters of culture in India and Pakistan attest to this. He has visited Dilli Haat and taught his art to school-children. He is friendly and voluble (not unusual) and patiently demonstrates his art to me in stages.

First, he lays a wax solution on silk (china silk is what is available in Pakistan), using a medium-thick paintbrush. What is remarkable is that he does so in very fine lines, and his outlines are filled in not by the laying of thick paint washes but by several of this thin lines running parallel within the space to be filled. When this dries, he paints over it with color. Again, this sounds ordinary until you look at his paintings closely and see that he achieves shading effects that are quite unexpected of the medium.

I will reiterate to you that I really would not look twice at this work in a market setting. However, the artist sells me three small paintings through a very simple technique—he shares with me his satisfaction, his joy at being able to do this work and his pride in the product. I choose two small paintings to gift, very simple little pieces, and then he states to me quietly, “This is my masterpiece.” It is a bird of paradise, copied from similar paintings done by his ancestor in the Mughal court (this is a hereditary art). I am not moved by the painting; but I really want a piece of this man’s joy and his pleasure in his own creativity. I buy the bird of paradise as a souvenir of that feeling.

IV

Eight animated people and a table full of pizza and pasta fill two hours of a cold winter evening with news of the mundane and the missing.

This is one of Islamabad’s hip cafes. I am meeting a group of new Pakistani friends and colleagues I met at a conflict transformation workshop in New Delhi earlier this year. Our conversation is meaningful because we are not talking about Kashmir or nuclear weapons or foreign policy. We are exchanging news of ourselves and others.

“Did you hear any more from her?”

“I saw him last at this seminar. I thought he would be here today.”

“How is your health at this time?”

“Where can I buy books?”

“I love to read her books. They bring back moments of my own life.”

“But I could not stomach this particular rendition.”

“You know I really cannot digest mozzarella.”

“We would have taken you to eat desi food but you are a vegetarian. And this is Pakistan.”Again. And again. And again, this weekend, I ask and am asked: why is it so difficult to replicate this easy camaraderie in our high politics?

V

A house run over with children between eighteen months and five years. Women friends seated around a table drinking tea. I enter this storybook image, and the group adjourns to a more formal space, as yet uncluttered by playing children.

Beautiful rugs, fine upholstery and classy furniture tell me that the occupant, my friend, is a person of taste. A pair of framed embroidery squares catch my eye. Later, asked about them, she tells us that she bought them in the bazaar for a pittance. As she looked at the fine work, she thought about the women bent over their embroidery frames in poor lighting. What could the vendor be paying them for their work when his selling price was so low? Moved, she framed the pieces in honor of the work done by these faceless, voiceless women.

The rest of our conversation is scattered. Mostly I am just an audience to mothers’ tales of their children, an intruder in a reunion of very close friends. It is a short intrusion, happily, and the one thing I will take from it is the story of the two framed embroidered squares, and my friend’s compassionate heart.

Family reunion

This year marks twenty-five years since I acquired family in Islamabad. The high point of this trip for me was getting to spend time with them and meeting those members of the family that I had not met before.

What makes people family? Our story has been told before, so I will not repeat it here. But it seems to me that family is built not on ties of blood, nor those of marriage, nor even by the tying of rakhis. Even love and affection are not enough. I think family is based on the will to be family and to do the hard work of keeping those relationships secure. At the twenty-five year mark, and with four children who have known me long before we met, I think we can claim to have had that will and done that work.What did I do in Islamabad, I am asked. I did ‘do’ lots of things. But my best memories will not be of things ‘done’ but moments shared. Family sitting around a dining-table eating excellent apples. Being introduced to friends. Watching children negotiate with each other over tic-tac-toe and who should sit where in a jeep. Playing ‘hide and seek’ with the little girl who wants to join her cousins in making friends with me but does not want to actually talk with me. Listening to exchanges about people I don’t know and lists of things I don’t have to do. Being present when ordinary choices are made and routine appointments kept. Learning the routines of the week and the rhythms of each person’s day. Watching the children transformed from cherubs in a photograph to individuals with preferences and distinctive traits.

My life would have been so much poorer without this dimension.

Bazaar diplomacy

It is around noon. We set out on a shopping expedition with a list where items appear and disappear like markings on Harry Potter’s magic map of Hogwarts.

“I would really like this.”

“We can try this here, but it is better there.”

That is too much information for me to process. The full alert position of my senses and brain cells is causing overload and jamming! So I say, “Well, maybe I can get it another time.”

“But I would really like this.”

“We can try this here, but it is better there.”

“Well, maybe I can get it another time.”

“But I would really like this.”

“We can try this here, but it is better there.”

“Well, maybe I can get it another time.”It’s a wonder I am not unceremoniously dumped from the car all day!

There is some political nonsense about Pakistan not granting ‘Most Favoured Nation’ (MFN) status to India. Nonsense it is, because in every Pakistani store I go to, India is the most favored nation. Prices drop when we don’t ask, drop further when my companion asks, and drop still further when I add my voice to the list. More importantly, merchandise is displayed with patience and with the pride reserved for one showing family photographs to a visiting relative.

MFN status means that I am going to get my Pakistani salwar kameezes after all. It is almost one o’ clock in the afternoon, but the store-keeper says, “You are from India. You are returning Monday? I will give it to you today after 9.” And yes, he will also quickly shrink the fabric for me as well. With that assurance, I shop with abandon choosing two lengths that to me—and I hope to others in Madras and Delhi—will not look Indian at all. He finishes the job early and when I go to collect the outfits, gifts me a wall-hanging with his store’s name and contact information on it. And also, he points out, “The Mohenjo-daro bull.” I am delighted with the thought of having the contact information for an Islamabad cloth store and tailor in Madras. That’s my kind of regional cooperation!

We adjourn to a gift store where a quick look around the handicrafts and gifts reveals that none of them are easy to pack. We linger in the music section of the store. My MFN status is reinforced here too, as sales clerks eagerly peel the cellophane off compact discs so I might listen to them and choose. When I don’t choose any, befuddled, I feel a little guilty. But we return later and buy several so that guilt is finally alleviated.

At this store, one clerk comes to assist me when I want to choose a couple of PTV serials to take back and watch. One choice is easy—Dhoop Kinare which was everyone’s favourite in the late 1980s. For the other, I am more indecisive, not knowing whether I can trust the clerk’s taste, the photographs on the cover or the two-three names I know to help me in my choice. Happily, when I go home, my choice is approved by everyone. That is a relief.

Our next halt is a craft store. We start by looking at shawls, then look at more shawls, then look at embroidered panels and cushion covers and then at onyx, stone and wood carving, and finally, back to the shawls and embroidery. As I try and juggle the sensory overdose with trying to remember people for whom I must buy gifts, my friend realizes that I am about to crash with the effort. She ushers me out of the store to catch my breath and we leave with what we have chosen for me. The result: no gifts purchased for anyone, making for a guilty return to town in a few days.

What people who do not like shopping do not understand is that shopping in a new country is a way of learning many things about the country. The array of goods and services teaches you what is made there and what is not. Window shopping or browsing tells you about the way in which people treat each other. The transaction itself teaches you about business practices, currency and in this instance, how people feel about your country. You watch people walk around the market and you see the food stalls and you learn what is snack food and how they eat. The prices you encounter tell you something about the state of the economy. Now, you may not be thread these into a social science thesis, but you certainly come away with an experience that sitting in a conference room, tourist bus, museum or formal living room will not give you.

We leave Super Market and head out to Kohsar. Islamabad is a lot like South Delhi with its perfectly planned sectors. Each sector has its own commercial area that caters both to its everyday needs and then some. At the Kohsar market, my friend and I have some delicious crepes. The challenge of finding me vegetarian food is taking people repeatedly to European-style eateries and cafes. I have no objection to this, being hard-pressed to find western food I like in Madras. A quick lunch and we pick up the day’s agenda again, including visits and a radio show!

Making waves

In my life I have done some strange and unexpected things. In India, I have always been constrained by the weight of other people’s impressions and expectations and still at 40, when I finally feel free to please myself, they stay with me. The places that free me (in my mind) remain special to me always.

One of these was Urbana, where a dear friend cum surrogate mother corralled me into modeling sarees for a fund-raiser. Another was New Haven where my body finally asserted its right to dance.

Most recently, last week in Islamabad, I was on the radio, being interviewed by the host of a popular Western music show. When she told me it would be broadcast live, I worried about my innate genius for putting my foot in my mouth, knowing that once I was introduced as an “Indian” visitor, there were no small consequences for it. But the host was so gracious, that it was a wonderful experience and I had a lot of fun doing it. We played songs from the 1960s and 1970s and she let me choose, which is a departure from her usual style. The talk ranges from mangoes to Indian cities and festivals to summer reading. Her idea is a simple, superb one—to explore the shared quotidian universe of middle class, English-speaking India and Pakistan.

The station is Power 99 and its enterprising owners are always willing to try new program formats or new projects. Their enthusiasm is palpable when I meet them as well. And sooner or later, we are in that “Why is it so hard for us to get along as states when we do so well as people?” discussion. People ask me that because I get introduced as an international relations or South Asia expert. But on this, unable to reproduce the official discourse as rationale, I can only join them in their lament.

Power 99 is planning to go online, and I look forward to the breaking of this barrier also. I want to listen to them on my computer at home, if only to add another skein to the fabric of this friendship.

Vantage points

My niece says we simply must go to Dominico. I am a little intrigued at this Italian place-name but before I can ask her about it, I find out it is Damen-e-koh and she is a little girl in a tearing hurry!

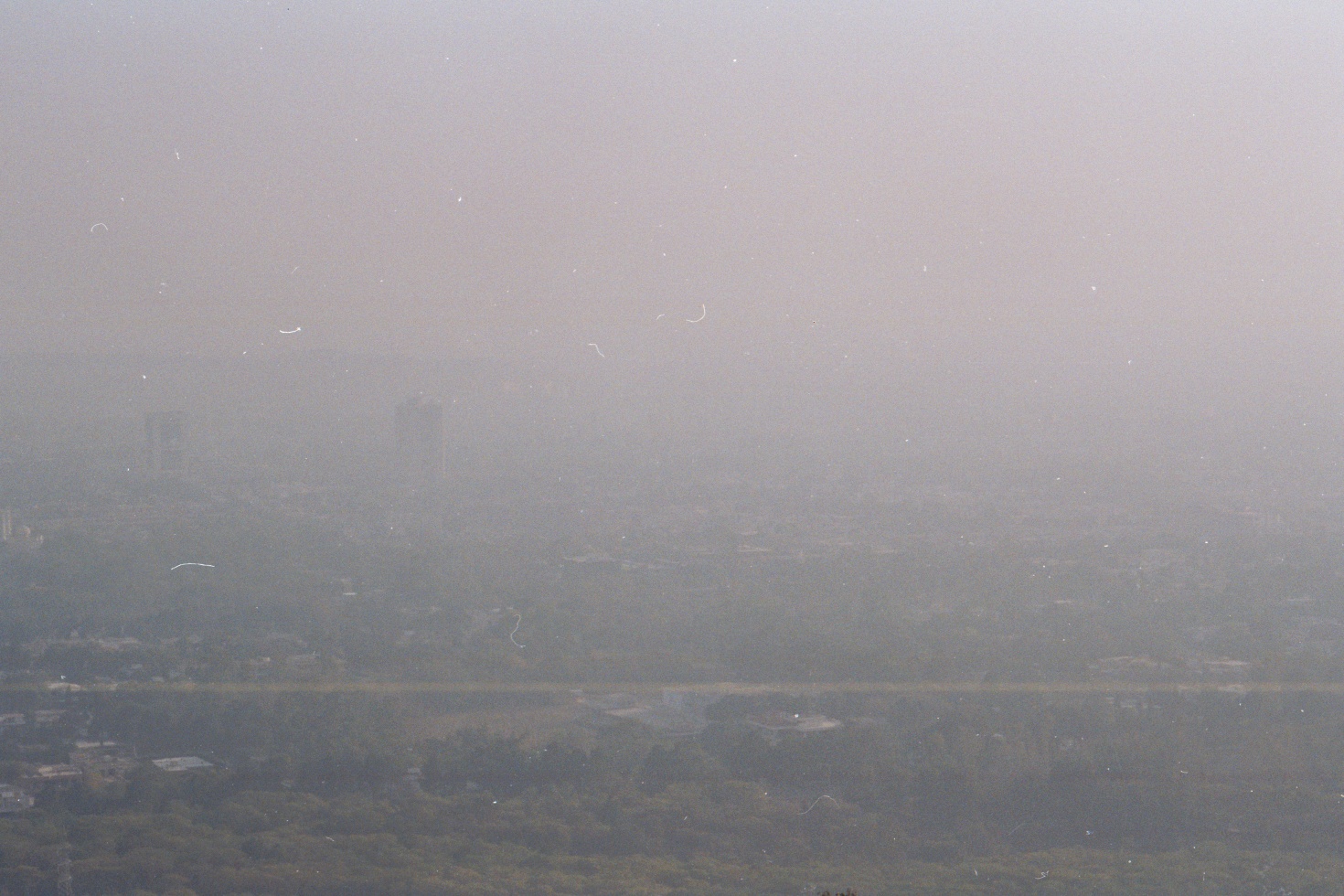

Daman-e-koh, a terraced garden in the Margallah Hills, offers a panoramic view of Islamabad. Its restaurant has photographs of SAARC leaders and other celebrities who have eaten there.

There are several terraces, currently under repair or construction, from which my nieces and nephews like to identify their house. This is the reason for the breathless excitement. However, that is not to be. The construction makes the railings look unsafe and we decide to abandon the project in favour of ice-cream.

To me, this is still a great outing. I have been able to come up to the hills. The view is still spectacular and the late lunch eaten in the winter sun the stuff of memories. I am not sure I know how to make the conversion, but I take many photographs of Islamabad with the hope of stringing them into one panoramic shot. After lunch we walk to a different side and the view of the hills from there is breathtaking.

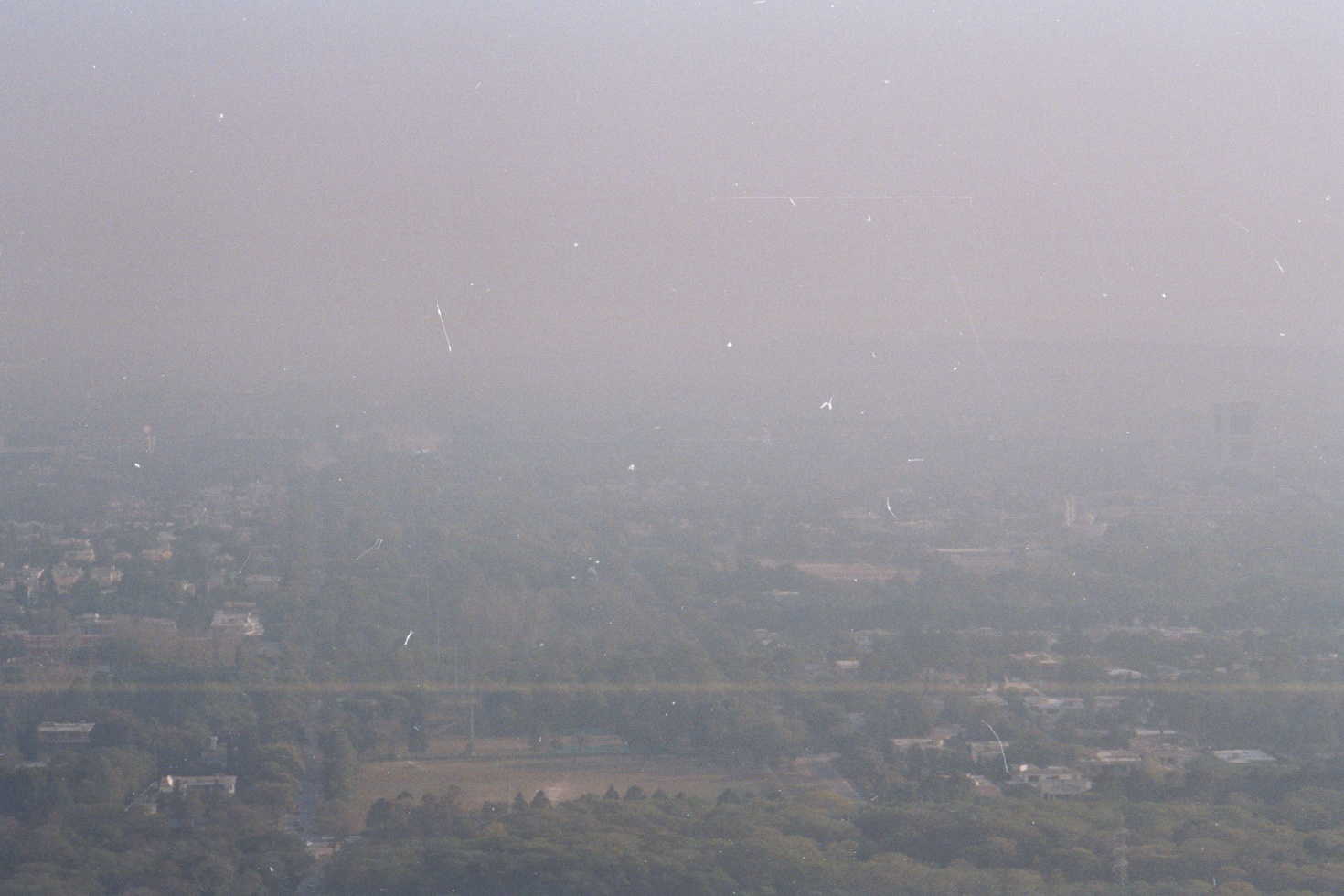

Above: My attempts at creating the components of a panoramic view of Islamabad from Daman-e-koh, December 12, 2004.

Excess luggage

Between all the paper acquired at the conference, books bought and books gifted to me, I need not have shopped for anything else to make my luggage incredibly heavy. My bags pass without comment in Islamabad, but in Lahore, the PIA agent tells me, “You have excess baggage but I am letting you go.” I say to him ruefully, “Thank you! What to do? There are so many beautiful things here and people have given me so many presents…”

What is harder to express in the laminate and aluminium setting of an airport is that what he is weighing is not the bulk of what you are taking back with you.

I am leaving Islamabad with a full heart. I have been shown and have received so much warmth and love that it enfolds me like soft layers of cotton-wool and silk. I cannot pack it and he cannot weigh it but it travels with me, and always will.

On the flight out from Lahore, they have forgotten to load vegetarian snacks and so I turn away my meal tray. The steward is genuinely upset: “You are a guest of Pakistan and you are not eating anything. You must at least have a little of the sweet.” It looks most unappetizing but he looks so hurt, I acquiesce. I reassure him; I took the precaution of eating a sandwich at the airport and Delhi is so close I can go eat dinner early, but nothing will reassure him. He apologizes each time he passes my seat.

The people sitting behind are furious. “You know half the passengers are Indians and they are mostly vegetarian. How does it look for them to fly PIA and not find anything to eat?!” I try and reassure them but they will not be mollified.

I am touched by everyone’s genuine regret. For years I have flown on American and European carriers that serve tasteless plasticene crap in the name of ‘Asian vegetarian food’ on long-distance international flights and quite often no vegetarian food at all on domestic flights. No one ever looks the least bit sorry or concerned; even as your eyes fill with hunger-induced self-pity. In the meanwhile, acidity sets in, ulcers build and your blood sugar drops, but no one cares. When I was a graduate student, I carried ‘tiffin dabbas’ (snack boxes) with me always and when I became marginally more solvent, always ate before boarding as a precaution and carried nuts or crackers.

In those years, flying Emirates or Sri Lankan Airlines made for unforgettable experiences. The food on Sri Lankan Airlines tastes as if it has just been cooked in the aircraft kitchen and the crew actually smiles at you like it comes naturally. This time my experience on PIA was good both ways. The crew were very friendly going out and on this same Lahore flight, they were attentive (even prior to the meal issue) in small ways that made it a very pleasant experience.

The hospitality I have enjoyed in Pakistan fills me with great doubt. How are we going to match this? When my Pakistani family visits, I worry that our hospitality at home will fall short—with our water shortages as a point of departure for all the ways in which that is likely. When my friends come, will they find the markets as friendly to Pakistanis as their markets are to Indians? Crew and passengers on PIA who seem to think that the aircraft is an extension of their own homes and must offer the same warm hospitality will not find the same on this side of the border.

The further south you come, the more torrid the climate, the less hospitable people seem to me. There is more than a touch of the miserly curmudgeon in most of us. I hope I am projecting my own limitations and that my experiences with people in South India are exceptionally bad. As I leave Pakistan, I want all my friends, old and new, to come visit us in India, but I am afraid we will be unable to match their generosity and hospitality.

Soft landing

The transition back to India (and real life) would have been hard were it not for a reunion with good friends in Delhi. Appetizers and a long lunch were followed by conversations under the winter sun. The cane chairs took root in the lawn as each person told their story of the last three years at length. My full heart was loath to say a second set of goodbyes in as many days but reality is relentless. As the sun began to set, our reunion broke up and I returned to work.

Joy, joy, joy, joy, joy

I have checked in and my flight to Chennai is delayed. I settle down with my laptop and am writing this account, when a couple of voices right behind me distract me. It is my guru, Sri Sri Ravi Shankar, and he is right behind me!

“Guruji!” I cry out. He looks up, smiling. I am beaming right back and there are no words in my mind, in my heart or on my lips. I am amused at my own speechlessness.

Transfixed, I put away my computer. I am not going to write while I can be watching him talk to others! Finally, everyone leaves, and I am still looking at him. As he has spoken to the others, he has been looking at me and smiling, maybe amused.

Everyone has left. I feel no need to introduce myself, so sure am I that he knows me. The connection is sure and ‘always on’ and the communication constant, with or without words.

He asks me if I am going to Bangalore. No, to Chennai, and I have just been to Pakistan.

What do I do? I tell him. I tell him I met him in Bangalore and volunteered my expertise. He asks for my card and asks his companion to give me one. He wants me to read about work being done by the Art of Living foundation in Kashmir.Words are now being exchanged. I am recording them here as if they matter or mattered. What I want to write about is the inexpressible joy of those moments that their memory still brings back. But it is intangible and inexpressible, and I cannot do it justice.

I call someone who will understand and who will share my joy. Can you believe he was standing right here? Just right behind me. I have met him and spoken with him twice this year. She says, “Nothing is a coincidence. You are truly blessed.”

I think of the love I have received in Pakistan, of the affection of my friends the day before, of the meaningful work I get to do everyday, and of meeting Guruji and speaking with him one on one so unexpectedly. I am truly blessed. I have no doubt of the abundance of grace and good fortune in my life and hope I can keep that knowledge alive within me at all times.

Swarna

Islamabad-Delhi-Chennai

December 7-20, 2004Return to my writing page or my home-page

Other links:

Since my photographs ended up mostly being of friends and family, you can find photographs of Islamabad here.

Palin's Travels contains some wonderful photographs, although only a couple pertain to places I mention.